FRITZ LEIBER’S SWORDS AND DEVILTRY

First things first. Let me get three things out of the way — a spoiler alert, a rebuttable presumption, and a delicate discussion.

The spoiler alert is needed because I’m going to recount the events in Fritz Leiber’s first book of the Fafhrd and Grey Mouser saga, Swords and Deviltry, published in 1970, collecting stories from 1960 to 1970, which were the (belated) origin stories of two characters he’d been writing about for more than 30 years, who would eventually fill a series of seven books written by Leiber himself.. If you’re not familiar with the saga, you may wish to quit reading here, and buy the book now and get started. Maybe you’re new to fantasy fiction, and just beginning to mine the veins of the Golden Age for writers such as Fritz Leiber.

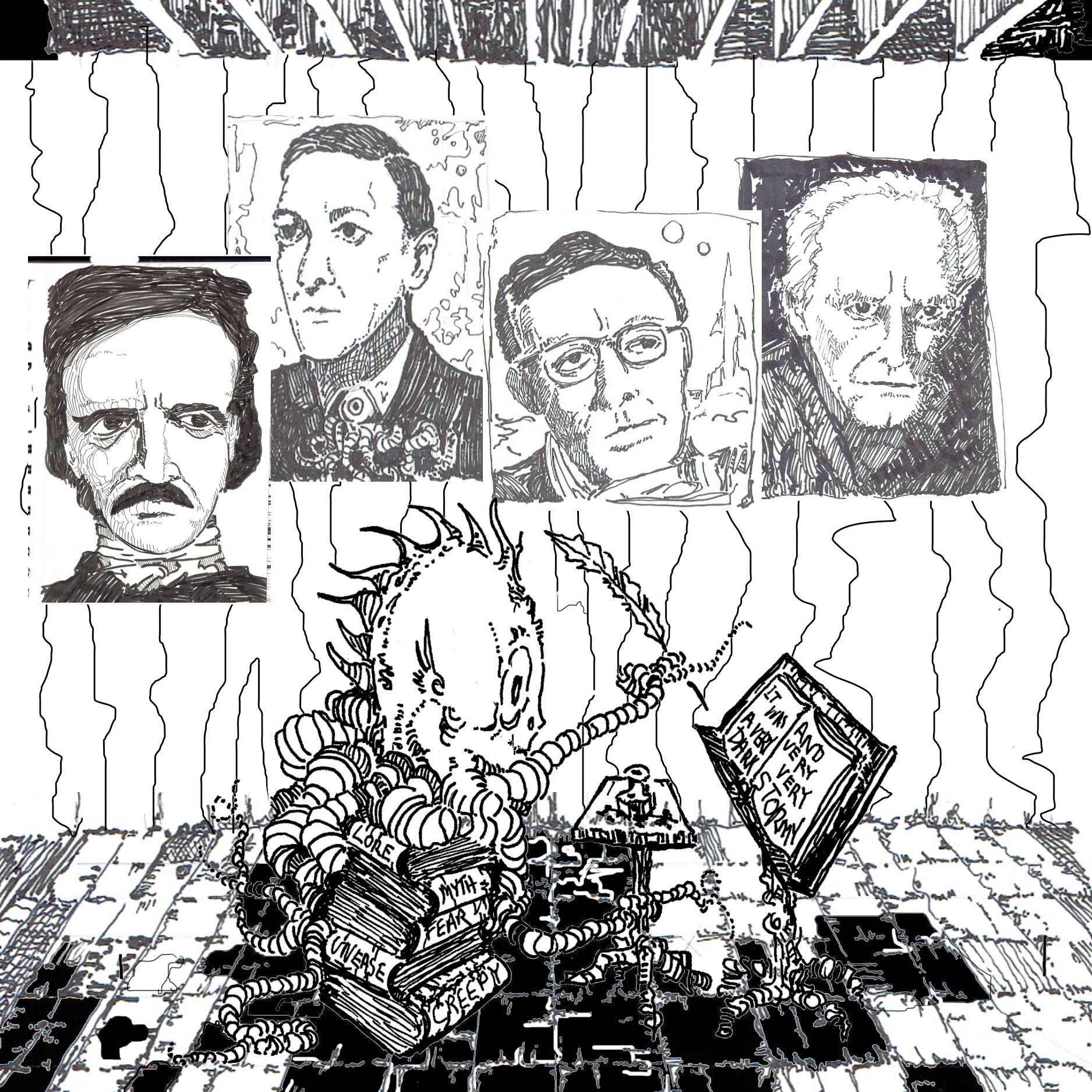

The rebuttable presumption: Fritz Leiber was the best genre writer of the 20th Century. There were people who sold more, garnered more awards, drew more attention to themselves, staked more of a claim within one genre or another — (for example, no one would seriously claim that Arthur Clarke was as adept at fantasy as he was at sf, or that Heinlein or Asimov were significant contributors to the genre of horror). Fritz Leiber had qualities which made him a master (if not an official Grandmaster) of horror, sf, and fantasy.

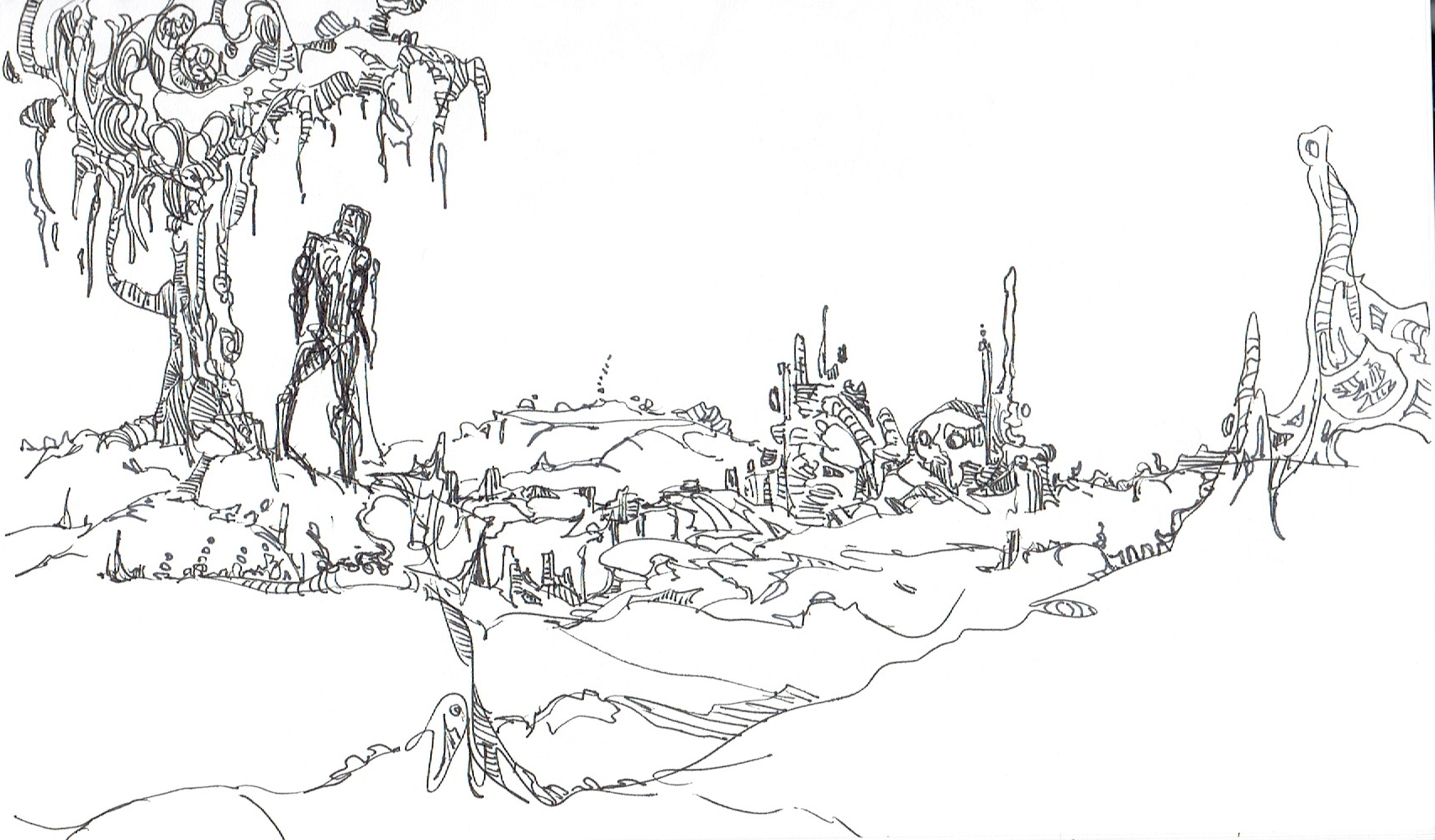

His fantasy credentials date from 1939, the year of the first publication appearance of Fafhrd and The Grey Mouser, and Leiber’s first professional fiction sale. On the timeline of 20th Century Fantasy, this was three years after the suicide of Robert E. Howard, and early in the twilight of Edgar Rice Burroughs’s writing career, with nearly 75% of his 80 novels having already been written and published.

Because of Howard and Burroughs, heroic fantasy or “Sword and Sorcery” would have survived even if Fritz Leiber had never gone near it, but I doubt that it would have the chance at respectability it has today.

Heroic fantasy is currently, and is probably destined to remain, a segment of fantasy fiction regarded as childish escapism for the emotionally stunted. If there are ever instances where it can be regarded as more than that, we have Fritz Leiber to thank.

The structure of Swords and Deviltry is simple, but elegant. The narrative is what was once called a “fix-up,” related stand-alone stories (in this instance three stories) presented in order to form a type of patched-together novel.

Story one is the tale of Fafhrd breaking away from his domineering mother (a literal witch) and smothering local girlfriend, becoming attached to an itinerant actress, Vlana, “love of his life,” and escaping his village.

Story two recounts The Grey Mouser losing his surrogate father, a wizard to which he is apprenticed, and becoming attached to a titled (and entitled) local girl, Ivrian, the “love of his life.”

In story three, these two couples encounter each other in the sprawling city of Lankhmar, the central metropolis of this fictional world of Nehwon. The two men form an immediate bond, strengthened when, in the course of the story (REMEMBER, SPOILER!) the two girls are hideously murdered at the behest of a dark magician. To wit, they are chewed to death by magic-controlled rats.

Now for the delicate discussion.

These girls had served their purpose, so they had to be eliminated. Happily married men don’t go Sword-and-Sorcerying around.

By giving the two heroes life-long loves, Leiber had inoculated the whole oeuvre against any speculation, either idle or subconscious or malicious, that the two bachelors had any but the most manly attachment. They were Barbarian Bros! Thieves with Honor! At no time during their wandering did they ever accidentally or purposefully “cross swords,” if you get my drift.

But it was also obvious that they couldn’t go on with these two girls in the way. The Grey Mouser’s love Ivrian, is neurotic and needy, a poster child for Daddy Issues, and requires pampering. Fafhrd’s love, Vlana, is becoming shrewish and demanding, insisting that he assume the burden of her vendetta against the Thieves’ Guild.

The girl’s deaths clear the way for the two heroes to pursue a lifetime of further adventures of thieving, mercenary work, and serving benevolent sorcerers. In the course of the seven books, the two will change and grow, but in Swords and Deviltry, the stage is set.

There’s much to love about Fritz Leiber and the unique blend of qualities he brought to his tales of Fafhrd and The Grey Mouser — the almost-but-never-quite-outrageous poetic writing style, the deft flavoring of philosophy, the satire (although I suspect that people like to label his work as satire at least partially as a self-defense against their embarrassment at enjoying the wizards and monsters), and his awareness of the deep currents of his characters’ psychological lives. All of this and more is on display in every page, and makes the tales of these Two Who Sought Adventure required reading.