(I wrote and posted on a previous version of my blog the following essay in 2012, on the occasion of the death of Ray Bradbury.)

Godspeed, Ray Bradbury

Posted on August 13, 2012 by cmsaplak

Here in Virginia kids have a pleasant little ritual during their last week of school (pleasant for me, anyway, if not for the kids). They receive the summer reading list for advanced placement English class. The rising eighth-graders were assigned to read two books, one of which they could choose from a list of about twenty, and one which was mandatory: Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451. I was delighted to see this choice.

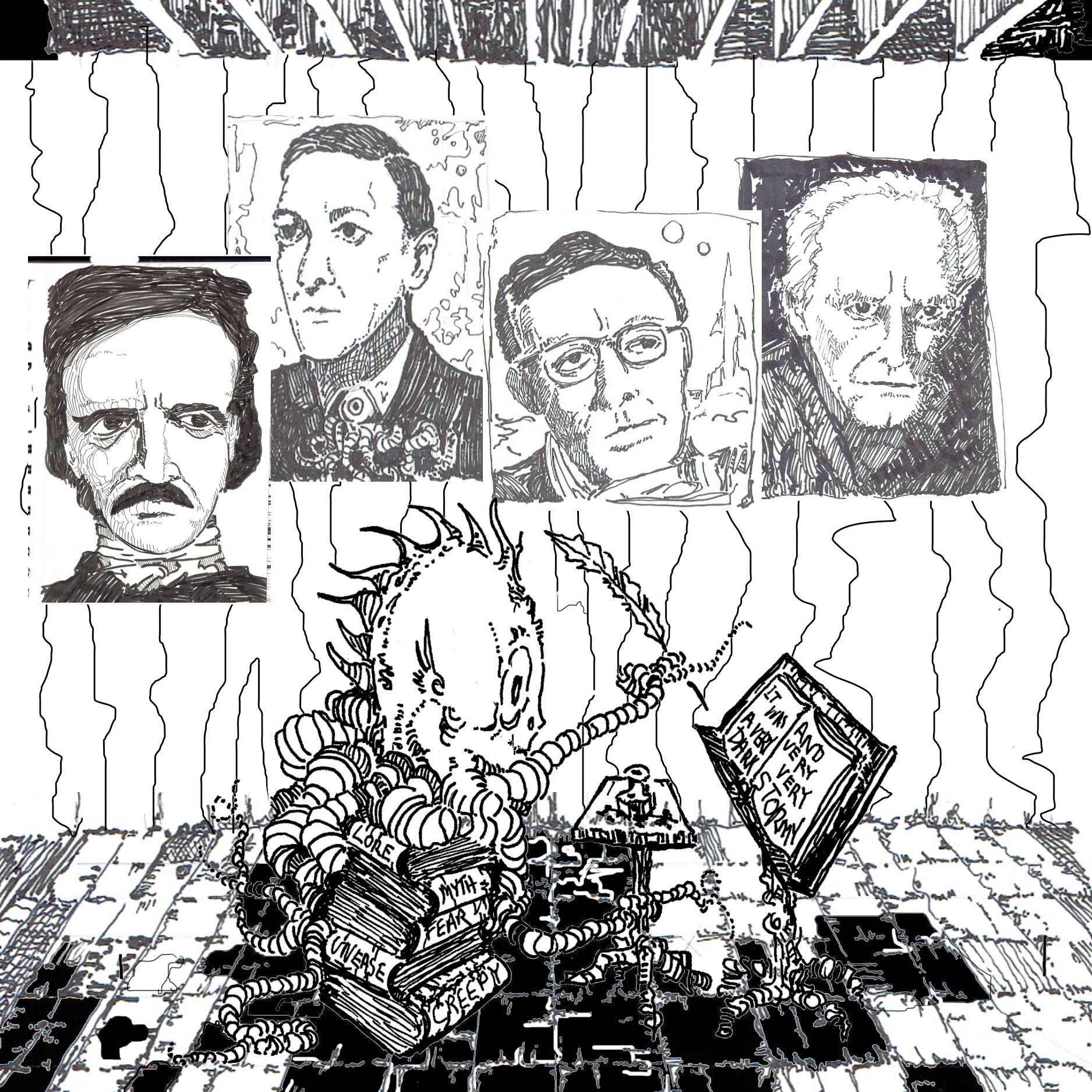

As a youth I worshiped Ray Bradbury. In high school I wrote my senior English term paper about him. I can still recall the opening line: “Ray Bradbury stands as one of America’s greatest writers.” I’m sure that serious scholars would frown upon that attitude. One isn’t supposed to enjoy or admire literature, one is supposed to dispassionately dissect it, as well as the people who produce it.

Ray Bradbury defied that attitude. He approached his writing as a joy, a sacred exultation in life. For Bradbury writing was a process of gathering and imagining beautiful things. Even when writing about the dystopian society in Fahrenheit 451 and the callous human explorers in The Martian Chronicles Bradbury wrote about our inability to fully appreciate the wonder about us, whether it was the wonder of a great book, or the wonder of a dead alien city. His attitude shone through in every line, making each word a profound gift to the lucky readers.

Ray Bradbury gave me (no, not directly — I never met the man) the best advice on writing I ever got. When starting out he set himself the goal of writing a story per week. When I was about thirty years old and decided that I needed to either get serious about writing or give it up, I tried to do the same. Of course, I fell short. At my peak I spent about a year of writing two stories every three weeks. And while Bradbury had, even in his early years, produced classics such as “Uncle Einar,” “Kaleidoscope,” and “Skeleton,” I found that at the end of my year I had produced several dozen stories of far lesser worth.

But among my heap of mediocrity, I had somehow produced a few works which didn’t outright embarrass. Some of the stories sold to pro magazines and anthologies. Some got good reviews. Some got published and recommended for awards.

And even the lesser works were valuable to me. When a would-be writer has a stack of several dozen of his own stories available to analyze, even stories which didn’t quite make it, one has what statisticians call “a good sample size.” I was able to see bad patterns, weaknesses in technique, or blind spots in my worldview. That stack of stories led me to ask myself several questions.

“Why do I have so many stories with framing devices which go nowhere? I like ’em — but the people who buy stories don’t see the point to many of them, besides the fact that they inflate my word count.”

“Why do I have so many stories where a protagonist is in an impossible situation, then fails? Shouldn’t I have some plots in which the protagonist at least tries to ‘protag’?”

“Why do I never have any female main characters?”

“Why do I seem to have so many stories which are either: a) around 1000 words, or b) over 8000 words? Magazine editors like to populate each issue with several mid-length stories which are neither too short to develop much impact, nor too long to buy from a beginner.”

That process of self-criticism led me to make some much needed changes in my approach, and although I’ve never developed beyond the stage of being a hit-or-miss writer, I spent the next few years doing far less missing and far more hitting.

As I was buying the copy of Fahrenheit 451 for my son, on the evening of 5 June, the lady at the bookstore and I had a nice little conversation about Ray Bradbury — how we had both read him as youths, how much his books meant to us. As we two strangers were recounting with pleasure his gifts to us, on the other side of the continent, Mr. Bradbury passed away. He would have been 92 this August.

I know that Mr. Bradbury received his share of money, awards, fame, and recognition during his lifetime. I know that his works are acknowledged as cultural touchstones. What I do not know is if that coincidence of that day — having people he never met share a moment of joy in his gift to us — eased his passing. Do great writers have a sense of the energy of wonder flowing through them, to know that even as their bodies fail, their words and works live on, burning like strange bright stars in far-flung skies?